Authenticity 自然, Autonomy自主, Emancipation 自由: Chinese Struggles for Freedom in a Global Context

News vom 10.03.2025

Authenticity 自然, Autonomy自主, Emancipation 自由:

Chinese Struggles for Freedom in a Global Context¹

Sara Landa & Barbara Mittler

What does freedom mean in our conflict-ridden world today and how important are specific types of freedom, academic freedom among them, to society as a whole? Where and how do red lines appear, who defines them, who has the power to move or question them? What is the relationship between different claims to freedom? How difficult is it, today, to “think differently”? And finally: What is the state of freedom in different parts of the world today as well as in the past? What can we learn? These were the questions behind a set of lectures and workshops, concerts and exhibitions that all discussed the function of discourse, dissent and dispute, of positioning, polarization and perspective in the making and breaking of freedom(s) in the world. In focusing on the “will to freedom” evident in different sinophone perspectives, through a series of events and workshops with artists and thinkers from different parts of the sinophone world, the program was co-organized by the Worldmaking Project and the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences as part of the Wissenschaftsjahr Freiheit.

“Chenmo” 沉默, “Silence”, is the title of a sculpture by Chinese artist Wang Keping 王克平 (1949-) from 1979. It shows a face, its eye blinded, its mouth gagged, with features that immediately evoke Edvard Munch’s 1893 “Skrik”. With this powerfully expressive sculpture, Wang demands an engagement with China’s Cultural Revolution as a period of un-freedom at its most extreme. At the same time, his sculpture gives a voice to all those who have been silenced in China and elsewhere, then and now.

Almost half a century later, Chinese-German compositor Wang Ying 王颖 (1976-) is again engaging with both past and present constellations of un-freedom, in an even more explicitly global dialogue. By juxtaposing the ‘white-haired girl’ Xi’er from the Maoist model opera with the same title and Elsa, another ‘white-haired girl’ from Disney’s “Frozen”, in an interview that is constantly interrupted — censored— by the powers that be, Wang has her two female protagonists question different understandings of freedom, un-freedom and dependencies on different systemic forces and political as well as market structures.

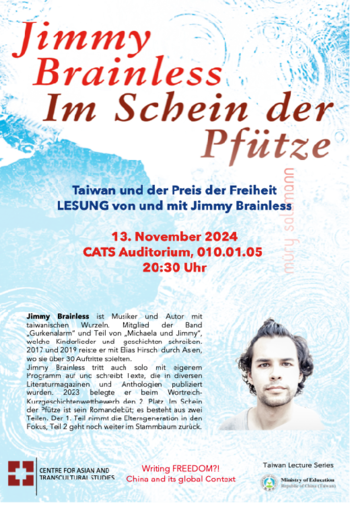

What can freedom mean in various sinophone contexts? Who can achieve freedom and for whom? Which role do the arts play in reflections on and activism for freedom in China? And how do Chinese artistic engagements with freedom as acts of worldmaking play into more globalized discussions? These were the questions posed in a series of events in Heidelberg that took place under the auspices of the BMBF Wissenschaftsjahr Freiheit in 2024. The events were conceptualized by members of the Heidelberg project Epochal Lifeworlds—Narratives of Crisis in cooperation with the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, the China-Schul-Akademie, as well as the KlangForum, the “Literaturherbst”, the Heidelberg Confucius Institute, und the CATS Taiwan Studies Program as well as the Ruperto Carola Lecture Series which discussed the crucial role of universities in creating a basis for the transmission of democratic values such as freedom. As they offer a discursive space, their task is to teach openness and mutual appreciation, to foster an interest in understanding the complexities and different positionalities in a specific matter at hand, and all this in order to develop an analytical and a critical eye—the very precondition for “proper critical debate.”

The series of events were conceptualized under the title Vom Willen zur Freiheit?! China im globalen Kontext to show the many facets and ambivalences of freedom, a concept that seems to grow more virulent and strong not in moments when it is protected and safe and therefore taken for granted, but rather when it is questioned, endangered, suppressed—in crisis. When freedom has to be defended, struggled for, against a variety of obstacles, against suppression, against silencing, across time and space, in past and present, in the People’s Republic of China, in Hong Kong, Taiwan or other parts of the sinophone world, it takes on ever more significant and variable meanings. Three core dimensions can be made out: freedom is conceived as “e-mancipation”—literally being taken out of somebody else’s hands—it allows the audience to follow his/her innermost goals, ziyou 自由; freedom appears as “autonomy”, being able to make one’s own decisions and values, zizhu 自主; and, thirdly, on a more personal level, freedom is enacted as the right to “authenticity” as being able to follow one’s nature, ziran 自然.

A series of multimedia formats, addressing audiences of different backgrounds and age groups, including literary recitations, concerts, film-screenings and lectures framed the twin exhibit entitled Mightier than the sword: Writing Freedom in China which featured calligraphy as an art-form that can stand ambivalently both for the powers of ideology and exclusion and the most liberal expression of self. In these multifarious events China’s search for freedom throughout her long history was illuminated as a long and enduring, harrowing as well as exhilarating story: the events featured calls for autonomous feminist and queer positions in the Sinophone worlds; they discussed (limited) possibilities to counter and subvert outright forms of violence and modes of censorship as well as hopes of opening up or upholding autonomous discursive spaces, away from the centers of power. The event series was thus able to delve into multiple dimensions of freedom in specific contexts reconsidering its broader global implications. At a time of radically shifting world orders and multiple crises, engaging this dialogue seems more important than ever.

Xiang Biao, one Chinese advocate of freedom who spoke in Heidelberg and who builds on something he calls “Self as Method”, began his Heidelberg lecture with the words: “Freedom is Space—if we do not actively courageously take action, this space will disappear; we have to work together — we need a common ground; freedom is not a theoretical lecture, not a concept, freedom is action.” His view echoes Hannah Arendt: for her freedom is not free WILL, it is PERFORMANCE. “In China,” Xiang Biao concluded, “to enact freedom, you must go out, go to the public, expose yourself… YES: Freedom implies a certain danger and a certain risk—if we do not face that danger probably we are not exercising our freedom: I hope you will join me to take a risk at certain point!“

¹ For an earlier report, see https://www.worldmaking-china.org/en/aktuelles/Exhibition-Invitation--Mightier-than-the-Sword_-Writing-Freedom.html. A more detailed description will be published in the Yearbook 2024 of the Academy of Sciences Baden-Württemberg: https://www.hadw-bw.de/publikationen/jahrbuecher-der-akademie Barbara Mittler & Odila Schröder “Vom Willen zur Freiheit?! China im globalen Kontext, Jahrbuch der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Heidelberg: Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften 2025, 133-160.